Sen. Jon Corzine, whose Wall Street expertise plays a key role in Democrats' strategy on corporate responsibility, led an investment banking firm that is being accused of inflating stock prices in the 1990s and contributing to the market crash.

Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle lately has kept Mr. Corzine at his side frequently as Democrats call on President Bush to get tougher with corporate executives who fraudulently inflate company earnings to boost stock prices.

"I think he's made a stellar contribution," said Sen. Paul S. Sarbanes, Maryland Democrat and author of a bill approved Monday by the Senate that would increase the penalties for corporate wrongdoers.

But Goldman Sachs, the firm that Mr. Corzine left as chairman in May 1999, has been a target of class-action lawsuits and accusations by a former broker who complained to the Securities and Exchange Commission that the investment house engaged in a scheme to force unwitting investors to pay artificially high prices for certain stocks.

Mr. Corzine, New Jersey Democrat, said he knew nothing about such schemes when he ran the firm from 1994 to 1999.

"I don't believe there is ever going to be anything that sticks about us at Goldman Sachs forcing anybody to buy anything," Mr. Corzine said in an interview. "Goldman Sachs never forced anyone to buy anything when I was chairman, I can tell you that."

But Nicholas Maier, who was syndicate manager of the Wall Street firm Cramer & Co. from 1996 to 1998, told SEC investigators in the spring that Goldman Sachs routinely forced him to buy stocks at inflated prices if he wanted to purchase shares of an initial public offering (IPO).

"Goldman, from what I witnessed, they were the worst perpetrator," Mr. Maier said. "They totally fueled the [market] bubble. And it's specifically that kind of behavior that has caused the market crash. They built these stocks upon an illegal foundation manipulated up, and ultimately, it really was the small person who ended up buying in."

For example, Mr. Maier told the SEC that Goldman Sachs would offer him shares of a new company's IPO at the initial, low price of $20 per share only if he agreed to purchase "aftermarket" shares of the same company at $100 each. In turn, he would sell the shares of the higher-priced stock to small investors.

"None of these aftermarket orders had anything to do with what I honestly valued a company to be worth," Mr. Maier said. "Goldman created the convincing appearance of a winner, and the trick worked so well that they seduced further interest from other speculators hoping to participate in the gold rush. The general public had no idea that these stocks were actually brought into the world at unnaturally high levels through illegal manipulation."

Mr. Bush on Monday said Wall Street went on a "binge" in the 1990s and now has a "hangover," a characterization that Mr. Corzine called "a diversion away from reality."

"What we had was a breakdown in corporate ethics and corporate responsibility that I don't think has anything to do with anything other than excessive focus on share price and managed earnings," he said.

Mr. Corzine retired from Goldman Sachs in 1999 after taking the firm public and receiving $320 million worth of its stock. He ran for the Senate in New Jersey in 2000, spending more than $60 million of his fortune to win the seat.

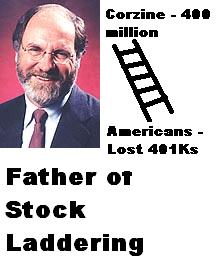

The bubble of high-priced technology stocks began to burst in March 2000. In August 2000, the SEC issued a warning against aftermarket sales, also known as "laddering."

"I've never even heard the term 'laddering' before," Mr. Corzine said yesterday. "We may have recommended on the analysis that we had that [a stock] was a 'good buy,' but you can't force anyone to buy anything. Investors make their choices about where people invest, unless they've asked somebody to manage their money."

Mr. Corzine was highly respected in his tenure at Goldman, and no one has accused him of encouraging "laddering" or even knowing about the practice. But Mr. Maier said it happened on Mr. Corzine's watch.

"For Corzine not to know of a common practice being utilized to generate and manipulate stock prices would be surprising," Mr. Maier said. "He was obviously there during this time. I definitively saw his company engaged in illegal activity."

The SEC would not comment yesterday on whether Goldman is under investigation. Mr. Maier said he has not spoken to the investigators in several months.

"They expressed to me that laddering is a trickier thing [to prove]," Mr. Maier said. "I will say it. They did it. They laddered. Whether the SEC can construct a case is a different story."

Asked whether he knew about an SEC investigation, Mr. Corzine said, "That could very possibly be; I'm not aware of it. I'm divorced from [Goldman] since 1999."

A class-action lawsuit filed in April 2001 accused Goldman Sachs and others of engaging in "laddering" on the initial sale of stock of NetZero, driving up the company's share price to artificially high levels.

In another class-action suit, shareholders of Buy.com have accused the firm and its underwriters, including Goldman Sachs, of engaging in a laddering scheme in its IPO in February 2000, after Mr. Corzine left Goldman. And investors of defunct online grocer Webvan.com have filed a similar suit in federal court concerning that firm's initial public offering in November 1999.

Another class-action suit filed last year says that underwriters, including Goldman Sachs, manipulated several IPOs since 1997, including at least six when Mr. Corzine was still at the helm of Goldman. Source: The Washington Times, July 17, 2002; "Corzine tied to stock scheme") |